Which Of These Animals Is Considered A Model For Punctuated Equilibrium?

The punctuated equilibrium model (top) consists of morphological stability followed by rare bursts of evolutionary change via rapid cladogenesis. In contrast, phyletic gradualism (below), is a more gradual, continuous model of evolution, with equilibrium states separated by jump phases.

In evolutionary biology, punctuated equilibrium (also called punctuated equilibria) is a theory that proposes that once a species appears in the fossil record, the population will get stable, showing little evolutionary change for most of its geological history.[i] This land of little or no morphological change is chosen stasis. When significant evolutionary change occurs, the theory proposes that it is mostly restricted to rare and geologically rapid events of branching speciation chosen cladogenesis. Cladogenesis is the process past which a species splits into two distinct species, rather than 1 species gradually transforming into some other.

Punctuated equilibrium is commonly contrasted with phyletic gradualism, the idea that evolution generally occurs uniformly by the steady and gradual transformation of whole lineages (anagenesis).[2]

In 1972, paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould published a landmark paper developing their theory and chosen it punctuated equilibria.[one] Their paper built upon Ernst Mayr's model of geographic speciation,[3] I. Michael Lerner's theories of developmental and genetic homeostasis,[4] and their ain empirical research.[five] [vi] Eldredge and Gould proposed that the caste of gradualism usually attributed to Charles Darwin[7] is most nonexistent in the fossil record, and that stasis dominates the history of most fossil species.

History [edit]

Punctuated equilibrium originated equally a logical issue of Ernst Mayr's concept of genetic revolutions by allopatric and especially peripatric speciation as applied to the fossil record. Although the sudden appearance of species and its human relationship to speciation was proposed and identified past Mayr in 1954,[3] historians of science generally recognize the 1972 Eldredge and Gould paper equally the ground of the new paleobiological research program.[viii] [9] [10] [11] Punctuated equilibrium differs from Mayr'south ideas mainly in that Eldredge and Gould placed considerably greater emphasis on stasis, whereas Mayr was concerned with explaining the morphological discontinuity (or "sudden jumps")[12] found in the fossil record.[viii] Mayr afterwards complimented Eldredge and Gould's paper, stating that evolutionary stasis had been "unexpected by nearly evolutionary biologists" and that punctuated equilibrium "had a major impact on paleontology and evolutionary biology."[eight]

A year before their 1972 Eldredge and Gould newspaper, Niles Eldredge published a paper in the journal Evolution which suggested that gradual evolution was seldom seen in the fossil record and argued that Ernst Mayr's standard mechanism of allopatric speciation might suggest a possible resolution.[v]

The Eldredge and Gould newspaper was presented at the Almanac Coming together of the Geological Gild of America in 1971.[i] The symposium focused its attention on how modern microevolutionary studies could revitalize diverse aspects of paleontology and macroevolution. Tom Schopf, who organized that yr's meeting, assigned Gould the topic of speciation. Gould recalls that "Eldredge's 1971 publication [on Paleozoic trilobites] had presented the only new and interesting ideas on the paleontological implications of the discipline—so I asked Schopf if we could present the paper jointly."[13] According to Gould "the ideas came mostly from Niles, with yours truly acting equally a sounding board and eventual scribe. I coined the term punctuated equilibrium and wrote most of our 1972 paper, but Niles is the proper beginning author in our pairing of Eldredge and Gould."[14] In his book Time Frames Eldredge recalls that afterwards much discussion the pair "each wrote roughly one-half. Some of the parts that would seem obviously the work of one of us were actually first penned by the other—I recall for example, writing the department on Gould's snails. Other parts are harder to reconstruct. Gould edited the unabridged manuscript for ameliorate consistency. Nosotros sent information technology in, and Schopf reacted strongly confronting information technology—thus signaling the tenor of the reaction it has engendered, though for shifting reasons, down to the present day."[15]

John Wilkins and Gareth Nelson accept argued that French builder Pierre Trémaux proposed an "anticipation of the theory of punctuated equilibrium of Gould and Eldredge."[sixteen]

Prove from the fossil record [edit]

The fossil record includes well documented examples of both phyletic gradualism and punctuational development.[17] Equally such, much debate persists over the prominence of stasis in the fossil record.[18] [19] Before punctuated equilibrium, nearly evolutionists considered stasis to be rare or unimportant.[eight] [20] [21] The paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson, for example, believed that phyletic gradual development (called horotely in his terminology) comprised xc% of evolution.[22] More modern studies,[23] [24] [25] including a meta-analysis examining 58 published studies on speciation patterns in the fossil tape showed that 71% of species exhibited stasis,[26] and 63% were associated with punctuated patterns of evolutionary change.[27] According to Michael Benton, "information technology seems clear then that stasis is common, and that had non been predicted from modern genetic studies."[17] A paramount example of evolutionary stasis is the fern Osmunda claytoniana. Based on paleontological evidence it has remained unchanged, even at the level of fossilized nuclei and chromosomes, for at to the lowest degree 180 million years.[28]

Theoretical mechanisms [edit]

Punctuational change [edit]

When Eldredge and Gould published their 1972 paper, allopatric speciation was considered the "standard" model of speciation.[1] This model was popularized by Ernst Mayr in his 1954 paper "Alter of genetic surround and evolution,"[3] and his classic volume Brute Species and Evolution (1963).[29]

Allopatric speciation suggests that species with large fundamental populations are stabilized by their large volume and the process of gene flow. New and even beneficial mutations are diluted by the population's big size and are unable to reach fixation, due to such factors equally constantly changing environments.[29] If this is the example, then the transformation of whole lineages should be rare, as the fossil record indicates. Smaller populations on the other hand, which are isolated from the parental stock, are decoupled from the homogenizing furnishings of gene flow. In addition, pressure level from natural selection is specially intense, as peripheral isolated populations exist at the outer edges of ecological tolerance. If most evolution happens in these rare instances of allopatric speciation so evidence of gradual evolution in the fossil record should exist rare. This hypothesis was alluded to past Mayr in the closing paragraph of his 1954 paper:

Rapidly evolving peripherally isolated populations may exist the identify of origin of many evolutionary novelties. Their isolation and comparatively small size may explain phenomena of rapid development and lack of documentation in the fossil record, hitherto puzzling to the palaeontologist.[three]

Although punctuated equilibrium generally applies to sexually reproducing organisms,[30] some biologists have applied the model to not-sexual species like viruses,[31] [32] which cannot exist stabilized by conventional gene menstruum. Equally time went on biologists like Gould moved away from hymeneals punctuated equilibrium to allopatric speciation, peculiarly every bit bear witness accumulated in back up of other modes of speciation.[2] Gould, for example, was particularly attracted to Douglas Futuyma's work on the importance of reproductive isolating mechanisms.[33]

Stasis [edit]

Many hypotheses have been proposed to explain the putative causes of stasis. Gould was initially attracted to I. Michael Lerner's theories of developmental and genetic homeostasis. Yet this hypothesis was rejected over time,[34] every bit evidence accumulated against information technology.[18] Other plausible mechanisms which have been suggested include: habitat tracking,[35] [36] stabilizing selection,[37] the Stenseth-Maynard Smith stability hypothesis,[38] constraints imposed past the nature of subdivided populations,[37] normalizing clade selection,[39] and koinophilia.[40] [41]

Show for stasis has also been corroborated from the genetics of sibling species, species which are morphologically indistinguishable, merely whose proteins have diverged sufficiently to advise they accept been separated for millions of years.[42] Fossil testify of reproductively isolated extant species of sympatric Olive Shells (Amalda sp.) also confirm morphological stasis in multiple lineages over three 1000000 years.[43] [44]

According to Gould, "stasis may emerge as the theory's most of import contribution to evolutionary science."[45] Philosopher Kim Sterelny in clarifying the pregnant of stasis adds, "In claiming that species typically undergo no further evolutionary modify in one case speciation is consummate, they are non claiming that there is no change at all between one generation and the next. Lineages do change. Merely the change between generations does not accumulate. Instead, over time, the species wobbles most its phenotypic mean. Jonathan Weiner's The Nib of the Finch describes this very process."[46]

Hierarchical development [edit]

Punctuated equilibrium has also been cited as contributing to the hypothesis that species are Darwinian individuals, and not just classes, thereby providing a stronger framework for a hierarchical theory of evolution.[47]

Common misconceptions [edit]

Much confusion has arisen over what proponents of punctuated equilibrium really argued, what mechanisms they advocated, how fast the punctuations were, what taxonomic scale their theory practical to, how revolutionary their claims were intended to be, and how punctuated equilibrium related to other ideas like saltationism, quantum evolution, and mass extinction.[48]

Saltationism [edit]

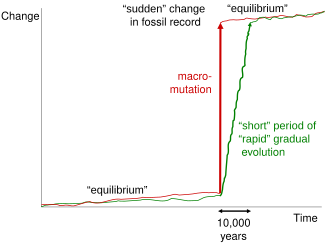

Alternative explanations for the punctuated pattern of evolution observed in the fossil record. Both macromutation and relatively rapid episodes of gradual evolution could give the appearance of instantaneous change, since 10,000 years seldom registers in the geological tape.

The punctuational nature of punctuated equilibrium has engendered possibly the near confusion over Eldredge and Gould's theory. Gould'south sympathetic treatment of Richard Goldschmidt,[49] the controversial geneticist who advocated the thought of "hopeful monsters," led some biologists to conclude that Gould'due south punctuations were occurring in single-generation jumps.[50] [51] [52] [53] This interpretation has frequently been used by creationists to characterize the weakness of the paleontological tape, and to portray gimmicky evolutionary biology every bit advancing neo-saltationism.[54] In an oftentimes quoted remark, Gould stated, "Since we proposed punctuated equilibria to explain trends, it is infuriating to be quoted again and over again by creationists—whether through design or stupidity, I practise non know—as admitting that the fossil record includes no transitional forms. Transitional forms are generally defective at the species level, but they are abundant between larger groups."[55] Although there exist some argue over how long the punctuations concluding, supporters of punctuated equilibrium generally place the figure betwixt 50,000 and 100,000 years.[56]

Quantum development [edit]

Quantum evolution was a controversial hypothesis advanced by Columbia University paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson, regarded by Gould equally "the greatest and well-nigh biologically astute paleontologist of the twentieth century."[57] Simpson's theorize was that according to the geological record, on very rare occasions evolution would proceed very apace to course entirely new families, orders, and classes of organisms.[58] [59] This hypothesis differs from punctuated equilibrium in several respects. First, punctuated equilibrium was more small in telescopic, in that it was addressing evolution specifically at the species level.[24] Simpson'south thought was principally concerned with evolution at higher taxonomic groups.[58] 2nd, Eldredge and Gould relied upon a different machinery. Where Simpson relied upon a synergistic interaction between genetic drift and a shift in the adaptive fitness landscape,[60] Eldredge and Gould relied upon ordinary speciation, especially Ernst Mayr's concept of allopatric speciation. Lastly, and perhaps about significantly, breakthrough evolution took no position on the issue of stasis. Although Simpson acknowledged the existence of stasis in what he called the bradytelic mode, he considered it (along with rapid evolution) to be unimportant in the larger scope of evolution.[61] In his Major Features of Evolution Simpson stated, "Evolutionary change is so almost the universal rule that a land of motility is, figuratively, normal in evolving populations. The country of rest, equally in bradytely, is the exception and it seems that some restraint or strength must be required to maintain information technology." Despite such differences between the two models, before critiques—from such eminent commentators every bit Sewall Wright as well as Simpson himself—have argued that punctuated equilibrium is picayune more than quantum development relabeled.[62] [63]

Multiple meanings of gradualism [edit]

Punctuated equilibrium is often portrayed to oppose the concept of gradualism, when it is really a course of gradualism.[64] This is because even though evolutionary change appears instantaneous between geological sedimentary layers, change is still occurring incrementally, with no groovy change from 1 generation to the next. To this stop, Gould subsequently commented that "About of our paleontological colleagues missed this insight considering they had non studied evolutionary theory and either did non know about allopatric speciation or had not considered its translation to geological fourth dimension. Our evolutionary colleagues also failed to grasp the implication(s), primarily because they did not think at geological scales".[14]

Richard Dawkins dedicates a chapter in The Blind Watchmaker to correcting, in his view, the wide confusion regarding rates of alter. His first point is to argue that phyletic gradualism—understood in the sense that evolution gain at a single uniform speed, called "constant speedism" past Dawkins—is a "caricature of Darwinism"[65] and "does not actually exist".[66] His 2d statement, which follows from the commencement, is that once the extravaganza of "constant speedism" is dismissed, we are left with one logical alternative, which Dawkins terms "variable speedism". Variable speedism may besides be distinguished one of two ways: "discrete variable speedism" and "continuously variable speedism". Eldredge and Gould, proposing that evolution jumps between stability and relative rapidity, are described as "discrete variable speedists", and "in this respect they are genuinely radical."[67] They assert that evolution generally gain in bursts, or not at all. "Continuously variable speedists", on the other paw, accelerate that "evolutionary rates fluctuate continuously from very fast to very dull and stop, with all intermediates. They run across no particular reason to emphasize certain speeds more than others. In particular, stasis, to them, is just an extreme case of ultra-tedious development. To a punctuationist, in that location is something very special about stasis."[68]

Criticism [edit]

Richard Dawkins regards the credible gaps represented in the fossil record as documenting migratory events rather than evolutionary events. According to Dawkins, evolution certainly occurred simply "probably gradually" elsewhere.[69] However, the punctuational equilibrium model may notwithstanding be inferred from both the observation of stasis and examples of rapid and episodic speciation events documented in the fossil tape.[70]

Dawkins also emphasizes that punctuated equilibrium has been "oversold by some journalists",[71] but partly due to Eldredge and Gould'southward "later writings".[72] Dawkins contends that the hypothesis "does non deserve a particularly big mensurate of publicity".[73] It is a "minor gloss," an "interesting but minor wrinkle on the surface of neo-Darwinian theory," and "lies firmly within the neo-Darwinian synthesis".[74]

In his volume Darwin's Dangerous Thought, philosopher Daniel Dennett is especially critical of Gould'south presentation of punctuated equilibrium. Dennett argues that Gould alternated between revolutionary and conservative claims, and that each fourth dimension Gould fabricated a revolutionary statement—or appeared to do and then—he was criticized, and thus retreated to a traditional neo-Darwinian position.[75] Gould responded to Dennett's claims in The New York Review of Books,[76] and in his technical volume The Structure of Evolutionary Theory.[77]

English professor Heidi Scott argues that Gould's talent for writing vivid prose, his utilise of metaphor, and his success in building a popular audience of nonspecialist readers contradistinct the "climate of specialized scientific soapbox" favorably in his promotion of punctuated equilibrium.[78] While Gould is celebrated for the color and energy of his prose, as well as his interdisciplinary cognition, critics such as Scott, Richard Dawkins, and Daniel Dennett take concerns that the theory has gained undeserved credence among non-scientists because of Gould's rhetorical skills.[78] Philosopher John Lyne and biologist Henry Howe believed punctuated equilibrium's success has much more to exercise with the nature of the geological record than the nature of Gould's rhetoric. They state, a "re-analysis of existing fossil data has shown, to the increasing satisfaction of the paleontological community, that Eldredge and Gould were correct in identifying periods of evolutionary stasis which are interrupted by much shorter periods of evolutionary change."[79]

Some critics jokingly referred to the theory of punctuated equilibrium as "evolution by jerks",[80] which reportedly prompted punctuationists to describe phyletic gradualism as "evolution by creeps."[81]

Darwin's theory [edit]

The sudden appearance of well-nigh species in the geologic tape and the lack of testify of substantial gradual modify in most species—from their initial appearance until their extinction—has long been noted, including by Charles Darwin who appealed to the imperfection of the tape equally the favored explanation.[82] [83] When presenting his ideas against the prevailing influences of catastrophism and progressive creationism, which envisaged species being supernaturally created at intervals, Darwin needed to forcefully stress the gradual nature of development in accordance with the gradualism promoted by his friend Charles Lyell. He privately expressed business concern, noting in the margin of his 1844 Essay, "Amend begin with this: If species really, subsequently catastrophes, created in showers world over, my theory simulated."[84]

It is often incorrectly assumed that he insisted that the rate of change must exist constant, or nearly then, but even the first edition of On the Origin of Species states that "Species of different genera and classes have not changed at the aforementioned charge per unit, or in the same degree. In the oldest tertiary beds a few living shells may however be found in the midst of a multitude of extinct forms... The Silurian Lingula differs merely little from the living species of this genus". Lingula is amidst the few brachiopods surviving today just besides known from fossils over 500 million years sometime.[85] In the fourth edition (1866) of On the Origin of Species Darwin wrote that "the periods during which species have undergone modification, though long as measured in years, have probably been short in comparison with the periods during which they retain the same form."[86] Thus punctuationism in general is consistent with Darwin's formulation of development.[84]

Co-ordinate to early versions of punctuated equilibrium, "peripheral isolates" are considered to be of critical importance for speciation. Even so, Darwin wrote, "I tin by no means hold ... that immigration and isolation are necessary elements.... Although isolation is of peachy importance in the production of new species, on the whole I am inclined to believe that largeness of area is yet more than important, peculiarly for the production of species which shall prove capable of enduring for a long period, and of spreading widely."[87]

The importance of isolation in forming species had played a significant part in Darwin's early on thinking, as shown in his Essay of 1844. Simply by the time he wrote the Origin he had downplayed its importance.[84] He explained the reasons for his revised view as follows:

Throughout a great and open area, non simply will there exist a greater chance of favourable variations, arising from the big number of individuals of the aforementioned species there supported, but the conditions of life are much more circuitous from the large number of already existing species; and if some of these species get modified and improved, others will accept to be improved in a corresponding degree, or they will exist exterminated. Each new form, also, equally soon as it has been improved, volition be able to spread over the open and continuous area, and will thus come into competition with many other forms ... the new forms produced on large areas, which have already been victorious over many competitors, volition be those that will spread most widely, and will give rise to the greatest number of new varieties and species. They will thus play a more important role in the changing history of the organic world.[88]

Thus punctuated equilibrium is incongruous with some of Darwin'due south ideas regarding the specific mechanisms of evolution, only generally accords with Darwin'southward theory of evolution by natural choice.[84] [89]

[edit]

Contempo work in developmental biology has identified dynamical and physical mechanisms of tissue morphogenesis that may underlie abrupt morphological transitions during evolution. Consequently, consideration of mechanisms of phylogenetic change that have been found in reality to exist non-gradual is increasingly mutual in the field of evolutionary developmental biology, particularly in studies of the origin of morphological novelty. A description of such mechanisms can exist found in the multi-authored volume Origination of Organismal Form (MIT Press; 2003).

Language change [edit]

In linguistics, R. Grand. W. Dixon has proposed a punctuated equilibrium model for language histories,[90] with reference particularly to the prehistory of the indigenous languages of Australia and his objections to the proposed Pama–Nyungan linguistic communication family there. Although his model has raised considerable interest, it does not command majority support within linguistics.[91]

Separately, contempo work using computational phylogenetic methods claims to show that punctuational bursts play an of import factor when languages split up from i another, accounting for anywhere from x to 33% of the full divergence in vocabulary.[92]

Mythology [edit]

Punctuational development has been argued to explain changes in folktales and mythology over time.[93]

See also [edit]

- Speciation

- Adaptive radiation

- Catastrophe theory

- Convergent evolution

- Court Jester Hypothesis

- Critical juncture theory

- Evolutionary capacitance

- Cistron orders

- Koinophilia

- Punctuated equilibrium in social theory

- Punctuated gradualism

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d Eldredge, Niles and Southward. J. Gould (1972). "Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism" In T.J.K. Schopf, ed., Models in Paleobiology. San Francisco: Freeman Cooper. pp. 82-115. Reprinted in N. Eldredge Fourth dimension frames. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Printing, 1985, pp. 193-223. (second draft, third final draft, Published draft)

- ^ a b S. J. Gould (1982) "Punctuated Equilibrium—A Different Fashion of Seeing." New Scientist 94 (Apr. 15): 137-139.

- ^ a b c d Mayr, Ernst (1954). "Change of genetic surroundings and development" In J. Huxley, A. C. Hardy and Due east. B. Ford. Evolution as a Process. London: Allen and Unwin, pp. 157-180.

- ^ Lerner, Israel Michael (1954). Genetic Homeostasis. New York: John Wiley.

- ^ a b Eldredge, Niles (1971). "The allopatric model and phylogeny in Paleozoic invertebrates". Evolution. 25 (1): 156–167. doi:10.2307/2406508. hdl:2246/6568. JSTOR 2406508. PMID 28562952.

- ^ Gould, South. J. (1969). "An evolutionary microcosm: Pleistocene and Recent history of the land snail P. (Poecilozonites) in Bermuda". Bull. Mus. Comp. Zool. 138: 407–532.

- ^ Rhodes, F. H. T. (1983). "Gradualism, punctuated equilibrium and the Origin of Species". Nature. 305 (5932): 269–272. Bibcode:1983Natur.305..269R. doi:10.1038/305269a0. PMID 6353241. S2CID 32953263.

- ^ a b c d Mayr, Ernst (1992). "Speciational Development or Punctuated Equilibria." In Albert Somit and Steven Peterson The Dynamics of Evolution. New York: Cornell University Press, pp. 21-48.

- ^ Shermer, Michael (2001). The Borderlands of Science. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 97-116.

- ^ Geary, Dana (2008). "The Legacy of Punctuated equilibrium." In Warren D. Allmon et al. Stephen Jay Gould: Reflections on His View of Life. Oxford: Oxford Academy Press, pp. 127-145.

- ^ Prothero, D. (2007). "Punk eek, Transitional Formsand Quote Miners." In Evolution: what the fossils say and why it matters. New York: Columbia University Printing, pp. 78–85.

- ^ Schindewolf, Otto (1936). Paldontologie, Entwicklungslehre und Genetik. Berlin: Borntraeger.

- ^ Gould, Due south. J. (2002). The Construction of Evolutionary Theory . Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 775. ISBN978-0-674-00613-3.

- ^ a b S. J. Gould (1991). "Opus 200" Natural History 100 (August): 12-18.

- ^ Eldredge, Niles (1985) Time Frames: The evolution of punctuated equilibria. Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 120.

- ^ Wilkins, John S.; Nelson, 1000. J. (2008). "Trémaux on species: A theory of allopatric speciation (and punctuated equilibrium) before Wagner" (PDF). History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. xxx (two): 179–206. PMID 19203015.

- ^ a b Benton, Michael and David Harper (2009) Introduction to Paleobiology and the Fossil Record New York: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 123-124.

- ^ a b Futuyma, Douglas (2005). Evolution. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, p. 86.

- ^ Erwin, D. H. and R. L. Anstey (1995) New approaches to speciation in the fossil record. New York : Columbia University Press.

- ^ S. J. Gould 2002. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge MA: Harvard Academy Printing, p. 875.

- ^ Wake, David B.; Roth, G.; Wake, G. H. (1983). "On the trouble of stasis in organismal evolution". Journal of Theoretical Biological science. 101 (2): 212. Bibcode:1983JThBi.101..211W. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(83)90335-ane.

- ^ Simpson, G. G. (1944). Tempo and Mode in Evolution. Columbia Academy Press. New York, p. 203.

- ^ Campbell, N.A. (1990) Biological science p. 450–451, 487–490, 499–501. Redwood City CA: Benjamin Cummings Publishing Visitor.

- ^ a b S. J. Gould, & Eldredge, Niles (1977). "Punctuated equilibria: the tempo and mode of evolution reconsidered." Archived 2018-05-08 at the Wayback Machine Paleobiology 3 (ii): 115-151. (p.145)

- ^ McCarthy, T. & Rubridge, B. (2005) The Story of Earth and Life. Cape Boondocks: Struik Publishers. ISBN 1-77007-148-2.

- ^ de Brito Neto, S. M.; Fernando Alves, E.; Cavalcante east Almeida Sá, Mariana (2017). "Speciation in existent time and historical-archaeological and its absence in geological time". Academia Journal of Scientific Enquiry. doi:10.15413/ajsr.2017.0413 (inactive 28 February 2022). ISSN 2315-7712.

{{cite periodical}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2022 (link) - ^ Erwin, D. H. and Anstey, R. L (1995). "Speciation in the fossil record." In Erwin, D. H. & Anstey, R. 50. (eds). New Approaches to Speciation in the Fossil Tape. Columbia Academy Printing, New York, pp. 11–39.

- ^ Bomfleur, B.; McLoughlin, S.; Vajda, V. (March 2014). "Fossilized nuclei and chromosomes reveal 180 million years of genomic stasis in imperial ferns". Science. 343 (6177): 1376–1377. Bibcode:2014Sci...343.1376B. doi:10.1126/science.1249884. PMID 24653037. S2CID 38248823.

- ^ a b Mayr, Ernst (1963). Animal Species and Evolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Eldredge, Niles and S. J. Gould (1997). "On punctuated equilibria (letter)." Science 276 (5311): 337-341.

- ^ Nichol, S.T, Joan Rowe, and Walter M. Fitch (1993). "Punctuated equilibrium and positive Darwinian evolution in vesicular stomatitis virus." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences ninety (Nov.): 10424-28.

- ^ Elena S.F., V.S. Cooper, and R. Lenski (1996). "Punctuated Evolution Acquired by Pick of Rare Benign Mutations." Science 272 (June 21): 1802-1804.

- ^ Futuyma, Douglas (1987). "On the function of species in anagenesis". American Naturalist. 130 (three): 465–473. doi:x.1086/284724. S2CID 83546424.

- ^ S. J. Gould 2002. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, p. 39.

- ^ Eldredge, Niles; Gould, S. J. (1974). Reply to Hecht. Evolutionary Biology. Vol. 7. pp. 305–306. doi:ten.1007/978-i-4615-6944-2_8. ISBN978-1-4615-6946-half-dozen.

- ^ Niles Eldredge (1989). Time Frames. Princeton University Printing, pp. 139-141.

- ^ a b Lieberman, B. S.; Dudgeon, S. (1996). "An evaluation of stabilizing selection as a mechanism for stasis". Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 127 (ane–four): 229–238. Bibcode:1996PPP...127..229L. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(96)00097-1.

- ^ Stenseth, N. C.; Maynard Smith, John (1984). "Coevolution in ecosystems: Red Queen evolution or stasis?". Evolution. 38 (4): 870–880. doi:10.2307/2408397. JSTOR 2408397. PMID 28555824.

- ^ Williams, G. C. (1992). Natural Choice: Domains, Levels and Challenges. New York: Oxford Academy Press, p. 132.

- ^ Koeslag, J. H. (1990). "Koinophilia groups sexual creatures into species, promotes stasis, and stabilizes social behaviour". Journal of Theoretical Biological science. 144 (1): 15–35. Bibcode:1990JThBi.144...15K. doi:ten.1016/s0022-5193(05)80297-8. PMID 2200930.

- ^ Koeslag, J.H. (1995). On the engine of speciation. J. theor. Biol. 177, 401-409

- ^ Maynard Smith, John (1989). Did Darwin Get it Right?. New York: Chapman and Hall. p. 126.

- ^ Gemmell, Michael R.; Trewick, Steven A.; Hills, Simon F. Thousand.; Morgan‐Richards, Mary (2019). "Phylogenetic topology and timing of New Zealand olive shells are consistent with punctuated equilibrium". Periodical of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 58 (one): 209–220. doi:x.1111/jzs.12342. S2CID 213493738.

- ^ Michaux, B. (1989). "Morphological variation of species through fourth dimension". Biological Periodical of the Linnean Guild. 38 (3): 239–255. doi:x.1111/j.1095-8312.1989.tb01577.10.

- ^ S. J. Gould 2002. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, p. 872.

- ^ Sterelny, Kim (2007). Dawkins vs. Gould: Survival of the Fittest. Cambridge, U.K.: Icon Books, p. 96.

- ^ Brett, Carlton Eastward.; Ivany, Linda C.; Schopf, Kenneth M. (1996). "Coordinated stasis: An overview". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 127 (1–iv): i–20. Bibcode:1996PPP...127....1B. doi:x.1016/S0031-0182(96)00085-5.

- ^ S. J. Gould (1992) "Punctuated equilibrium in fact and theory." Archived 2018-01-26 at the Wayback Automobile In Albert Somit and Steven Peterson The Dynamics of Development. New York: Cornell University Printing. pp. 54–84.

- ^ Southward. J. Gould (1976). "The Render of Hopeful Monsters," Natural History 86 (June/July): 22-30.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst (1982). Growth of Biological Thought. Harvard University Press, p. 617 Archived 2016-06-23 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ Maynard Smith, John (1983) "The genetics of stasis and punctuations." Archived 2010-12-06 at the Wayback Machine Annual Review of Genetics 17: 12.

- ^ Ruse, Michael (1985) Sociobiology, Sense or Nonsense? New York: Springer, p. 216.

- ^ For reply see Due south. J. Gould Construction. 2002, pp. 765, 778, 1001, 1005, 1009; R. Dawkins The Blind Watchmaker. 1996, pp. 230-36; and D. Dennett Darwin'southward Dangerous Idea. 1996, pp. 288-289.

- ^ Hanegraaff, Hank (1998). The Face That Demonstrates the Farce of Development. Nashville, TN: Word Publishing, pp. 40-45.

- ^ S. J. Gould (1981). "Evolution as Fact and Theory," Find two (May): 34-37.

- ^ Ayala, F. (2005). "The Structure of Evolutionary Theory" (PDF). Theology and Scientific discipline. 3 (1): 104. doi:10.1080/14746700500039800. S2CID 4293004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-09-23. Retrieved 2007-04-22 .

- ^ S. J. Gould (2007) Punctuated equilibrium. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, p. 26.

- ^ a b Simpson, Chiliad. G. (1944). Tempo and Style in Evolution. New York: Columbia Univ. Press, p. 206

- ^ Fitch, Westward. J. and F. J. Ayala (1995) Tempo and mode in evolution: genetics and paleontology fifty years after Simpson. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- ^ Simpson, G. M. (1953). The Major Features of Development Archived 2019-04-21 at the Wayback Machine. New York: Columbia Univ. Press, p. 390.

- ^ Simpson, G. Thousand. (1944). Tempo and Mode in Evolution. New York: Columbia Univ. Printing, pp. 205-206.

- ^ Wright, Sewall (1982). "Character change, speciation, and the higher taxa" (PDF). Evolution. 56 (three): 427–443. doi:10.2307/2408092. JSTOR 2408092. PMID 28568042. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-28.

- ^ Simpson, G. G. (1984) Tempo and Mode in Development. Reprint. Columbia University Press, p. xxv.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1996). The Blind Watchmaker. New York: Westward. W. Norton & Co., Chapter 9. (p. 224-252)

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1996). The Bullheaded Watchmaker. New York: Due west. W. Norton & Co., p. 227.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1996). The Blind Watchmaker, p. 228. Dawkins' exception to this rule is the non-adaptive evolution observed in molecular evolution.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1996) The Bullheaded Watchmaker, p. 245.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1996). The Blind Watchmaker, p. 245-246.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1996). The Blind Watchmaker, p. 240.

- ^ Cheetham, Alan; Jackson, Jeremy; Hayek, Lee-Ann (1994). "Quantitative genetics of bryozoan phenotypic evolution". Evolution. 48 (ii): 360–375. doi:10.2307/2410098. JSTOR 2410098.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1996). The Bullheaded Watchmaker, p. 250-251.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1996). The Bullheaded Watchmaker, p. 241.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1996). The Blind Watchmaker, p. 250.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1996). The Blind Watchmaker, p. 251.

- ^ Dennett, Daniel (1995). Darwin's Dangerous Idea. New York: Simon & Schuster, pp. 282-299.

- ^ Gould, S. J. (1997). "Darwinian Fundamentalism" The New York Review of Books, June 12, pp. 34-37; and "Evolution: The Pleasures of Pluralism" The New York Review of Books, June 26, pp. 47-52.

- ^ "Stephen Jay Gould, "Punctuated Equilibrium'southward Threefold History," 2002". 2019-10-19. Archived from the original on 19 October 2019. Retrieved 2022-02-16 .

- ^ a b Scott, Heidi (2007). "Stephen Jay Gould and the Rhetoric of Evolutionary Theory". Rhetoric Review. 26 (ii): 120–141. doi:ten.1080/07350190709336705. S2CID 144947503.

- ^ Lyne, John and Henry Howe "'Punctuated Equilibria': Rhetorical Dynamics of a Scientific Controversy". in Harris, R. A. ed. (2007). Landmark Essays on Rhetoric of Scientific discipline. Mahwah NJ: Hermagoras Press, p. 73.

- ^ Turner, John (1984). "Why nosotros demand evolution by jerks." New Scientist 101 (February. 9): 34–35.

- ^ Gould, S. J. and Steven Rose, ed. (2007). The Richness of Life: The Essential Stephen Jay Gould. New York: West. Due west. Norton & Co., p. 6.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1859). On the Origin of Species. London: John Murray, p. 301.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1871). The Origin of Species. London: John Murray, p. 119-120.

- ^ a b c d Eldredge, Niles (2006) "Confessions of a Darwinist." The Virginia Quarterly Review 82 (Jump): 32-53.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1859). On the Origin of Species. London: John Murray. p. 313.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1869). The Origin of Species. London: John Murray. 5th edition, p. 551.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1869). The Origin of Species. London: John Murray. 5th edition, pp. 120-121.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1869). The Origin of Species. London: John Murray. 5th edition, pp. 121-122.

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay; Eldredge, Niles (1993), "Punctuated equilibrium comes of age", Nature, 366 (6452): 223–227, Bibcode:1993Natur.366..223G, doi:x.1038/366223a0, PMID 8232582, S2CID 4253816

- ^ Dixon, R.M.W. (1997). The rise and autumn of languages Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing.

- ^ Bowern, Claire; Koch, Harold, eds. (2004-03-eighteen). Australian Languages. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Vol. 249. John Benjamins Publishing Visitor. doi:10.1075/cilt.249. ISBN9789027295118.

- ^ Atkinson, Quentin D.; Meade, Andrew; Venditti, Chris; Greenhill, Simon J.; Pagel, Marker (2008). "Languages Evolve in Punctuational Bursts". Science. 319 (5863): 588. doi:x.1126/scientific discipline.1149683. hdl:1885/33371. PMID 18239118. S2CID 29740420. ; Dan Dediu mail, Stephen C. Levinson, Abstract Profiles of Structural Stability Point to Universal Tendencies, Family-Specific Factors, and Aboriginal Connections between Languages, PLoS ONE,vii(9), 2012, e451982012.

- ^ Julien d'Huy, A Cosmic Hunt in the Berber sky : a phylogenetic reconstruction of Palaeolithic mythology. Les Cahiers de l'AARS, xv, 2012; Polyphemus (Aa. Thursday. 1137) A phylogenetic reconstruction of a prehistoric tale. Nouvelle Mythologie Comparée / New Comparative Mythology 1, 2013; Les mythes évolueraient par ponctuations. Mythologie française, 252, 2013, 8-12.

External links [edit]

- Punctuated Equilibrium - by Stephen Jay Gould

- Punctuated Equilibrium at 20 - by Donald R. Prothero

- Punctuated Equilibria? - past Wesley Elsberry, TalkOrigins Archive

- Scholarpedia: Punctuated equilibria - by Bruce Lieberman and Niles Eldredge

- All you need to know about Punctuated Equilibrium (almost) - past Douglas Theobald

- Enigmas of Evolution - by Jerry Adler and John Carey, Newsweek

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Punctuated_equalibrium

Posted by: smithockly1984.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Of These Animals Is Considered A Model For Punctuated Equilibrium?"

Post a Comment